-->

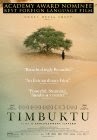

Timbuktu

is a dramatized pastiche of stories telling how the Jihadists changed everyday

life when they arrived in that area of Mali in Africa. The judge, Abdelkerim (Jafri), travels

on a motorcycle or a truck with his translator in tow announcing on a bull horn

new rules the citizens must follow in keeping with Sharia law, such as: no smoking, no football, and no music,

and women must cover their heads, hands, and feet. The citizens don’t like this, of course, and openly resist,

only finding out later that they will suffer punishment that is often extreme.

All of the examples are heartbreaking, but one

is highlighted to show the complexities of the law interacting with real

people. Kidane (Ahmed) is a humble

businessman who lives in a tent in the sand with his wife and daughter whom he

adores. He has also taken under

his wing the male child of a friend, a rebel who was killed fighting for a

cause. Kidane has Issan care for

his herd of nine cows, one of which—named GPS—is special because she is

pregnant. Kidane plans with his

wife’s encouragement to give that cow and the herd to Issan, the boy. This establishes his noble intentions,

which are in stark contrast with the petty “rules” of Abdelkerim.

Kidane is not your stereotypical Muslim; he is

respectful of his wife and values her advice, and he adores his daughter (God

has not blessed him with a son, but this girl is the light of his life). His wife wants to leave the area as

many of their friends and neighbors have, but he remains optimistic that the

current situation is temporary and that eventually all their friends will

return. He then chides her a bit

about missing her female friends, which she does not deny. (This interaction was a poignant

reminder of what the Jews experienced when Hitler was coming into power. Some bolted the country as soon as they

could, while others hoped that everything would work itself out.)

Unfortunately, Kidane’s cows must drink from

the river where Amadou the fisherman has his nets. Amadou worries when the cows get close to his nets, and one

day takes matters into his own hands.

This is a huge insult to Kidane, who, with his wife’s blessing, goes to

talk to Amadou. He tells his wife

where he is going, and heads out. Ominously,

he says, “And you know what I haven’t told you.” After this, we get a good picture of how Sharia Law

works—basically the accused has to plead his case with the judge, and the judge

metes out whatever punishment he thinks is deserved.

After all the crosscutting back and forth

between the stories, the writer/director Abderrhmane Sissako, presents an

account of the outcome for each one.

It is a brilliant exposé of Sharia Law and how it works, the

depersonalization it involves, and probably most importantly, the absence of

humanitarian reasoning in its considerations. So telling is a slight misgiving on the part of Abdelkerim

about Kidane’s daughter, which he expresses to his translator, but tells him

not to reveal what he says to Kidane.

Timbuktu

is a story well worth telling, with Sofiane El Fani’s cinematography lending

beauty and anguish to this well designed film. I am glad it received an Academy Awards nomination for Best

Foreign Picture.

An exotically filmed picture chronicaling

the horrors brought by the Jihadists to Timbuktu.

Grade: A By Donna

R. Copeland

No comments:

Post a Comment